Steven and I had stayed the previous night in Elkins, West Virginia, a town at the crossroads of not two but three scenic highways located in the Potomac Highlands amid the state's highest mountains. Getting on the road on what was the dreariest day yet of our trip, we headed south on a dotted road, i.e. one considered particularly scenic according to the AAA. The road bordered the Monongahela National Forest that had so caught our fancy the day before.

This Daily Travelogue is a labor of love for our families and friends at home and around the world. Prior to 2020, all our trips were documented on separate, yearly blogs which can be accessed below. Remember that clicking on any picture will open it for better viewing. Also, please consider adding your name at the end of any comments. Be safe, stay healthy, and stay connected.

Saturday, February 27, 2021

8/22: Elkins-Beckley, WV: Winding our Way thru West Virginia!

As the overcast skies cleared, we passed lots of lumber and millworks companies and the appropriately named hamlet of Mill Creek.

Steven didn't need much persuasion to stop at this home outside of Mugo with its unusual sculptures!

We'd first noticed quilt patterns on the sides of barns the day before.

Living in one of the country's top ski meccas as Colorado, I think we had blinders on when it came to acknowledging ski resorts existed in West Virginia. How ignorant we were as the area was just beautiful. If you love to ski, you just might want to consider staying in Elk Run or Snowshoe the next time you plan a ski vacation.

We turned on Highway 150, aka the Monongahela's Highland Scenic Highway toward the Hadley Wildlife Management Area. The 43-mile scenic byway was a chance to explore more of the state's back roads and some unusual formations.

From the Red Lick Lookout, we had a gorgeous view of the Greenbrier River Valley.

We read that these mountaintops were part of a special place with remnants of the red spruce forest that existed more than 10,000 years ago. The area's high elevation, cold weather, and geology had combined to make these mountain ridges a relic of the last Ice Age.

The tallest mountain here was Stony Creek at an elevation of 3,526 feet.

The Honeycomb Rocks in the national forest were named for the unique boxwork patterns found in the boulders. As you might imagine, early visitors were puzzled over the patterns wondering if they were messages left by unknown wanderers, evidence of space travelers, fossil impressions from the skin of a giant dinosaur, or even hieroglyphics from ancient Egypt!

About 340 million years ago, water, and wind left grains of quartz sand here and they eventually formed the sedimentary rock, sandstone. The mineral that held the sandstone together was kaolinite, a clay-like substance found in porcelain sinks, toothpaste, and makeup!

The filter effect: Over many years, water flowed through the sandstone fractures, carrying the iron mineral hematite through the sandstone which acted as a filter. This process was the same we use to make coffee! Hematite is the mineral form of iron and is used for steel in railroads, highways, buildings, and appliances.

Just as we've all noticed water spots on a glass probably due to a calcium buildup from hard water after it evaporates, the same process cemented the fractured sandstone back together. But in this case, instead of calcium, hematite did the job!

Rocks and minerals broke down over time due to sunlight, wind, and water. The sandstone, held together by the weaker kaolinite, wore away faster than the hematite boxwork.

The brightly colored mushroom was sitting in an egg carton for some reason!

Scientists thought that with the hematite stopping in the middle of this rock suggested it was on the edge of the fracture zone.

These honeycomb rocks were just another brilliant example of the beauty of nature that we were so privileged to witness.

We stopped next at the Williams River Scenic Overlook where we learned how much the land in front of us had changed. Black Mountain was so named because it had once appeared 'black' from the dense growths of spruce and hemlock forests. Before West Virginia's logging boom, red spruce trees covered more than 500,000 acres in the state's high country. How sad to learn that now the forest covers just five percent of its original range. Thankfully, though, the red spruce forest is making a comeback due to tree planting, better management, and other factors.

We were so lucky to be here at the perfect time to catch the profusion of wildflowers.

The highest point here was Big Spruce Knob at 4,673 feet.

A little to the right, the 'bump' to the right of the tree was the Red Spruce Knob, sitting at 4,703 feet.

We drove further in the national forest to the Cranberry Glades Botanical Area, named after the cranberry, an evergreen shrub or vine more at home in the far north of the US. The glades were one of the state's largest wetlands and looked like the bogs or 'muskegs' of the northern US or my native Canada. The Glades was designated as a National Natural Landmark in 1974.

I was not looking forward to spotting any black bears, West Virginia's state animal, and who also enjoy the glades!

Dense thickets of alder separated the openings with swamp forests of red spruce and hardwoods marking the edges. As the glades were around 3,400 feet above sea level and encircled by the Black, Cranberry, and Kennison mountains, the area was a haven for cold-loving plants and animals.

I hadn't known before that a cranberry plant that grew thick in the glades was under four inches tall. The plant's bright red berries were much more visible in the fall.

The soils of the Cranberry Glades contained large amounts of decaying plant material known as peat. These peat deposits were nearly 20 feet deep and provided an environment for many unusual life forms. Because pollen can be preserved in peat for thousands of years, scientists have been able to study the deposits to learn about ancient environments and climate change.

Did you notice the sign on the boardwalk indicating we were entering Bog Forest?!

Yew Creek:

Over 10,000 years ago, Ice Age glaciers pushed as far south as the Ohio River. When the ice retreated, plants and animals more suited to a warmer environment took advantage. The Glades was the southernmost home for many rare life forms.

A sign said that blue crayfish lived deep within the earth here, with their burrows having lots of tunnels anywhere from eighteen inches to six feet underground. I could hardly believe that more than 400 species benefit from all that tunneling and use crayfish burrows. The crayfish spreads nutrients from the topsoil to deeper layers. The crayfish variety found here was called a True Blue and remained that color for life, unlike other blue crayfish that change colors.

I think this pretty pink plant was a Canada Mayflower.

As we'd known from visits to other parks, dead trees in every stage of decay were still vital to living things. Birds, bats, and raccoons love to make their homes in hollow trees, and squirrels climb inside for shelter and to store food. Insects eat the tree's decaying wood and mosses and ferns grow on old trees and return vital nutrients to the soil so that decaying logs act as "nurseries for new seedlings."

Another idyllic West Virginia pastoral scene:

Just a few miles further on was Watoga State Park, West Virginia's largest. The Greenbrier River:

If you like to camp, Watoga looked like they had some pretty campsites and cabins.

We were relieved not to be driving this narrow four-mile-long road in icy conditions to the overlook as we might have ended up in the ditch!

We'd hoped to sit a spell and enjoy the view but the gnats forced a hasty retreat to the car.

The park office:

The CCC Worker statue, erected in memory of all the 'boys' who served in the Civilian Conservation Corps from 1933-1942, had been erected in 1999 by former CCC enrollees. They must have been a pretty advanced age then.

Next to the park office was the Civilian Conservation Corps Museum.

Camp Watoga, the CCC camp, was occupied by CCC Company 1525 S-2. The enrollees, under the direction of the Division of Forestry, lived in tents until the permanent buildings were being constructed. Their job included fire hazard reduction and blister rust control - no idea what that was. In 1934 the camp was transferred to the auspices of the National Park Service when Watoga became a state park.

Footlocker trunks were a standard issue for the men who came to work in the CCC camps across the country. They had a wooden frame, a strong metal exterior, and hinges. Most lockers were used by multiple men in the CCC but this one was used by Donald Wilson while he was on various assignments. His final one was at Watoga as a member of Camp Watauga Company from 1939-1940.

Crews working in the CCC camps ate three meals a day provided by the government in government-issued mess kits like these. As most workers came from families who struggled to put food on the table during the Great Depression, it helped their families who thus had one less mouth to feed at home.

The workers built roads, trails, cabins, administrative offices, a dam, and a swimming pool.

The hike around the park's West Lake was one of the narrowest paths we've ever been on! There was no real trail in much of the hike which made it more challenging or more fun, depending on one's point of view!

Though the sky was a brilliant shade of blue, we heard the ominous sounds of thunder the entire walk around the lake. We just hoped we'd still be dry when we reached the car!

We couldn't have timed the end of our walk any better as we reached our car just as the heavens opened!

We headed south next on Highway 219 from Mill Point to reach Droop Mountain Battlefield State Park. We didn't realize at the time we'd also pass the outside of Pearl S. Buck's birthplace in Hillsboro, West Virginia. Suellen: Remember my texting you way back last August about our seeing it? I sure didn't think it would take me this long to include the photo in this post!

The last few days we'd been lucky enough while driving on country roads to pass several barns with detailed quilt patterns painted on the sides. I think there was a guide showing where we could have found others - something for another time, perhaps!

Droop Mountain Battlefield was part of The Civil War Discovery Trail, which linked more than 300 sites in 16 states to inspire and to teach the story of the Civil War and its impact on America. The Trail, an initiative of the Civil War Trust, allowed visitors to explore battlefields, historic homes, railroad stations, cemeteries, parks and other destinations that bring history to life.

On November 6, 1863, the Federal army of Brigadier General William W. Averell attempted for the second time to disrupt the Virginia-Tennessee Railroad at Salem, Virginia. Averell and his troops faced the Confederate troops of Brigadier General John Echols. Throughout the morning, Echols’ smaller confederate army held the high ground and blocked the highway with artillery, but was later overwhelmed by the crushing advance of federal infantry on his left flank. Following the collapse of his lines, General Echols retreated south into Virginia with the remnants of his command.

General Averell waited until early December to lead a third and ultimately successful attack on the vital railroad. Operations in the Shenandoah Valley in the spring of 1864 drew remaining confederate troops out of West Virginia, thus leaving the new state securely under the control of the federal government for the remainder of the war.

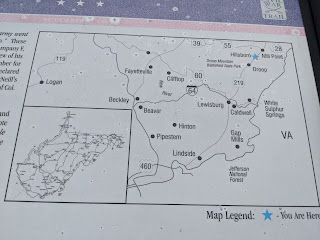

I couldn't remember the last time, if ever, we'd seen a a map where North was pointing at the bottom right and South was at the top left! It was drawn this way as it was from the viewpoint of General Averell's Union Army as it was traveling southwest.

Bands were great morale builders during the Civil War. They played under fire, as well as in camp, and while soldiers marched. In the infantry, there were about a dozen calls, and often twenty and more in the artillery and cavalry units. Drums were also used for calls - a veteran regiment could maneuver by drumbeat with NO spoken commands given!

This drum had been found by three local boys while tending to a wounded Confederate soldier after the battle. Believing they might be captured by approaching Union soldiers, they ran down the mountain and took the drum with them. After being in the possession of community families until 1997, it was finally donated to the state park for all to enjoy!

Droop Mountain was a critical battle because roads were vital to the movement of the artillery and supply wagons required to support armies. The Mountain was a high ridge on the main noth/south road that connected two major east/west crossings of the Alleghenies. Because of extensive views to the north and south, the summit of Droop Mountain was an ideal defensive position on the most important route in the region. Before the arrival of White men in the area, Indigenous people used the mountain's level top as a shortcut.

The monument honored both federal and union soldiers who had lost their lives at the Battle of Droop Mountain. With nearly 400 casualties on both sides, the battle at Droop Mountain was one of the largest battles in West Virginia and also the last significant one.

We spent a short time walking through the battlefield to get a sense of what had transpired so many years ago during the harrowing period in this country's history. I couldn't help but think how little the thick underbrush had obstructed the views on both sides and must have made communication so challenging.

Col. Augustus Moor led the 28th Ohio Infantry, a federal force, that was comprised of 1,175 German immigrants from the Cincinnati area along this ridge with the intent to crush the Confederate left flank. However, the force was stopped by a Confederate charge. With reinforcements from the 10th WV Infantry, the advance continued until the Confederate line broke.

The 19th Virginia Cavalry found themselves in the weakest point in the Confederate army's mountaintop position because of the terrain. Even so, when faced by almost 1,200 Federal troops, they charged and temporarily halted the advance until they had to fall back with heavy casualties. Learning that, I had to wonder what went through the minds of the brave men who watched their comrades suffer and die amid the agony of defeat.

The Confederate trenches looked impossibly shallow to hold adult men

Even knowing exactly what had transpired just feet away from where we stood, it was still so hard to grasp the horror of war the men on both sides experienced as it all looked so perfectly idyllic and peaceful.

The political sign supporting Governor Jim Justice reminded us we were certainly in Republican country and coal was king.

Lewisburg's Carnegie Hall was one of just three Halls in the US named for noted philanthropist and steel baron Andrew Carnegie who gave the town almost $30,000 for the construction of the Georgian Revival-style Lewisburg Female Institute in 1902.

Later known as the Greenbrier College, Carnegie Hall has since become a regional cultural center for the visual and performing arts.

The remains of 95 unknown Confederate soldiers had been laid to rest in the cross-shaped Old Confederate Cemetery. The men had fought in the Battle of Lewisburg on May 23, 1862. Their bodies had originally been laid out without any ceremony along the south wall of the town's Old Stone Church.

Their remains were removed from the churchyard after the war and interred in this moving cross-shaped grave that measured 80 feet long with a cross arm of 40 feet.

Andrew Lewis Park and the town itself was named for the general who organized the Virginia militia in 1774 for a campaign against the Shawnee Indigenous people.

Our last stop of the day was at the stunning Greenbrier Hotel in the town of White Sulphur Springs. The hotel's earliest guests came to “take the waters” to restore their health in 1778. By the 1830s the resort became prominent in the South for wealthy and powerful Southerners to annually congregate at the "village in the wilderness" during the summer months because the 2,000-foot elevation was a break from the heat and humidity in the lowlands.

Between 1830-1861, five sitting presidents stayed at what was affectionately known as The Old White, thereby demonstrating the resort's reputation as the place for the nation's most influential and powerful families. In 1914, Joseph and Rose Kennedy traveled down from Boston for their October honeymoon. Famed golfer Sam Snead in 1948 established The Greenbrier as one of the world's foremost golf destinations by being the resident golf pro. Jack Nicklaus added to the hotel's cachet by redesigning the golf course for the Ryder Cup. Pete Sampras was named The Greenbrier's first Tennis Pro Emeritus in 2014.

As Steven knows, I'm a sucker when it comes to ogling the world's grand hotels so he parked while I had a look around at where the world's beautiful people cavort!

As Steven joked over dinner, we certainly find a way to fill up our days while we travel. That was a long day even for us, though, as we still had another hour's drive to reach Beckley where we spent the night. But, once again we'd been thoroughly and completely charmed by all that we'd seen in West Virginia.

Next post: The country's newest national park, New River!

Posted on February 27th, 2021, from our home in Denver after a far too short visit from our elder daughter and her husband as they drove cross country from San Francisco to their new home in Brooklyn, New York. We are keeping our fingers crossed that we'll see them in the Big Apple in July en route to a beach vacation in Florida.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)