Steven and I wanted to visit the city of Greensboro in North Carolina last September to learn more about the four, brave, young, local men who led the change for desegregation more than sixty years ago when they sat down at their local Woolworth's lunch counter and asked to be served. Their act led to the eventual transformation of the Woolworth's into the International Civil Rights Museum.

First, though, some other images of Greensboro:

The elegant Blandwood Mansion had been the home of North Carolina Governor John Morehead and was built as a farmhouse in the late 18th century before being redesigned as an Italian villa in 1844. Blandwood was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1988 because it possessed national significance in commemorating the country's history.

Lunsford Richardson (1854-1919) co-owned a store on Greensboro's Elm Street, the main drag in town, where he developed a line of home remedies, one of which was Vick's VapoRub for the relief of the common cold. How well I remember my mother applying it to my chest when I was a child.

Powerful, powerful words and images - I urge you to click on the photo to make it bigger so you can see it more clearly.

I cannot possibly relate the countless injustices and horrors Blacks experienced particularly in the American Deep South during the last century. However, knowing that in 1939, two Black teenagers in Marion, Tennessee, were denied were denied due process of law, were treated less than citizens, and were hung; knowing that protesters endured water being sprayed on them that was so intense it literally removed bark from nearby trees; knowing that a 17 year-old non-violent protester was attacked by a police dog even though the police's stated role was and still is 'to protect and serve' is reprehensible.

An homage to Breonna Taylor AND all the other Black men, women, and children who have been killed at the hand of the police in America:

On February 1, 1960, four Black freshman students from North Carolina A&T University in Greensboro sat down at the city's Woolworth's segregated lunch counter and requested to be served. That simple request for equality sparked a generation to rally for social justice for Blacks in the American South. People throughout the United States, inspired by the 'Greensboro Four', conducted marches, sit-ins, and demonstrations to rid this country of segregation.

Walking down the stairs just as those four young men had done all those years earlier gave me chills up and down my spine. With each passing step, I wondered what we would see and, more importantly, feel.

Though we knew the original lunch counter had been dismantled in the face of protests, it was still a gut punch imagining what Blacks felt each time they walked down the steps and faced the counter knowing that only Whites would be served there.

Blacks could only order take out at the end of the counter.

Steven and I alone watched a re-enactment of what took place that day when David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Jibreel Khazan, and Joseph McNeil, each of whom had shopped since they were children in the same Woolworth's but had never eaten there wanted to challenge the Jim Crow laws of racial segregation in public facilities. They, of course, had no idea what would happen the next day in terms of being expelled from college, arrested, and beaten.

When the four local students tried to order food, some customers left in disgust and others supported them saying that Blacks should have demanded to be served long ago.

They sat for an hour - what began as just the four students grew to four more and more again. In ensuing days, students from other local colleges came to the Woolworth's lunch counter, sitting quietly doing their homework.

A group of White local high school students committed to continue the sit-in in support during the summer. Black employees from Woolworth's removed their work clothes and put on street clothes and sit at the counter in support of the students. More that 2,000 of Greensboro's adult Black community marched in support of the students including virtually every Black doctor, principal, teacher, and 26 ministers. The campaign dragged on for six months against Woolworth's.

The sit-in in Greensboro sparked similar activities in other Southern cities. What had begun as four young men sitting at the counter created a firestorm of change throughout the country. By the end of 1960, 75,000 students had taken part in sit-ins for social change. We learned that by 1963, there were 930 demonstrations in 115 cities just across 11 southern states. The result was more than 20,000 arrests of civil rights activists.

As The Greensboro Record reported on July 25th of 1960, "Faced with economic pressure - not so much from the loss of lunch counters and/or Black customers as from the loss of White customers who stayed away from the disruptions of protest - merchants in Greensboro, as in other communities challenged by sit-ins, quietly conceded." Woolworth's sought to keep the new status of serving Blacks quiet, and didn't allow photos to be taken, nor advertised a change in policy.

The direct actions of sit-ins resulted in a profound impact on not only cities and states but also corporations and small-scale entrepreneurs at their most vulnerable point - their bottom line. The realization was clear - upholding racist practices would take an economic toll, potentially leading to financial disaster. The price of denying civil rights to Blacks proved to be too costly for many businesses. It still took until June 13, 1963, however, for Greensboro's mayor, recognizing the community's commitment to the movement, to announce the city's endorsement of integration. Slowly but surely, over the next few years, lunch counters were integrated in the South - the 'Greensboro Four' had been victorious!

I read that while the action of the 'Greensboro Four' was an incredible act of courage, there had been previous sit-ins. In 1957, for instance, seven Blacks staged one at the segregated Royal Ice Cream Parlor in Durham, North Carolina. Perhaps you remember the mural depicting that in my last post? What made Greensboro different was "how it grew from a courageous moment to a revolutionary movement."

If you click on the photo to enlarge it, you will see the names of the donors who paid for the re-creation of the Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro so all future generations could witness how Blacks had been treated until four stood up and said, "No more."

We continued our tour of the museum, seeing a stone and brick reproduction of the actual Colored-Only entrance to the Greensboro Rail Depot, the major stop for trains heading from the northern states to the segregated South.

We were reminded how Blacks had to sit in designated sections of theaters and buses; had to drink from racially segregated water fountains; and use separate bathrooms.

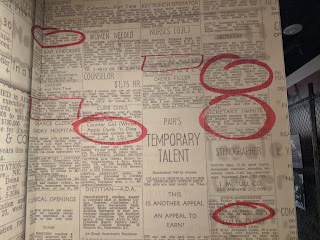

Company rules or hiring practices meant Blacks couldn’t apply for most visible positions. Circled in red were newspaper ads for jobs and accommodations for Blacks who were restricted to the most menial and physically demanding of jobs and living in the most poorly developed sections of town.

As Blacks traveled in the South, there were few hotels where they could stay and they had to order take out at restaurants that would not seat them. Prior planning was required to survive on the road. To avoid being caught without a place to stay or food to eat, Blacks sought out resources such as the secretive Green Book that identified 'safe houses' and facilities catering to them. The book spurred the creation of informal networks Blacks need to tap into when making travel plans.

The museum opened up at least my eyes to what Blacks also faced in regard to access to theaters and entertainment. Generally, they could watch the same production as Whites but were often limited to sitting in the balcony only. Opening equal access to theaters and entertainment became a priority for many in the civil rights era. Prominent minister and national political activist Jesse Jackson was a football star at North Carolina A&T in 1963 when he led students in marches and demonstrations to shut down Elm Street to demand the desegregation of theaters.

The museum pointed out that five Greensboro churches specifically were sympathetic to, and played active roles in, supporting local activism.

It was horrific to see the body of 14-year-old Emmett Till who, while visiting his grandmother and other Southern relatives from Chicago, was accused of whistling at a White woman in a store. After being beaten and shot, his corpse was weighted down in a 70-pound cotton gin fan and dumped in the Tallahatchie River.

High-powered hoses used against peaceful protesters:

Hardly a walk of fame but rather a reminder we should all be walking in the shoes of the 'Greensboro Four.'

As we left the museum, an employee was just placing this poster in the window of the incredible RBG or Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg who had fought for gender equality and civil rights. She had died three days earlier.

Steven and I then drove to the now renamed North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University where the Greensboro Four began their courageous march just over 60 years ago. Though the students had been expelled following their sit-in, the monument in front of the university seemed to celebrate their heroic actions. The university had also renamed dorms in honor of each student.

I couldn't leave Greensboro without being affected by all that we saw and heard about what four brave young men started by 'simply' sitting down at the lunch counter and expecting to be served like Whites. If you're ever anywhere near the city, I hope you will make a point of stopping at the International Civil Rights Museum that has been registered as an International Site of Conscience and one of the 14 major sites on the newly inaugurated US Civil Rights Trail. I assure you, you'll be glad you did.

Next post: Andy Griffith's Mayberry and the Blue Ridge Parkway from last September's road trip or Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota from our current road trip!

Posted on June 14th, 2021, from Minneapolis, Minnesota, just a day after Steven and I stopped at the newly named George Floyd Square in honor of the man who was killed while in police custody. Writing this post about the 'Greensboro Four' so soon after seeing first hand the signs, murals, and memorials about George's death has made me question how much life has changed for Blacks since the Woolworth's sit-in 61 years ago now.

No comments:

Post a Comment