It was only because Steven and I were unable to visit the Netherlands for several days to start off our trip as planned that we had extra time in Brussels and were, therefore, able to spend a day in Waterloo, located about ten miles south of Belgium's capital city. It was probably just as well we didn't realize at the outset that it would take 90 minutes on the metro and bus, with the latter stopping every few blocks all the way out to the boonies!

For all of us who lived through the tragic events of 9/11, it was evident that history can change course in just one day. The same could be said for June 18th, 1815, when Europe's destiny was decided on farm fields south of Brussels at the Battle of Waterloo when more than 40,000 men died or were injured in just one day's struggle that ended Napoleon's control and made England the 19th-century superpower.

In the distance was one of the most visible sights at Waterloo, Lion's Mound - more on that later in the post!

On June 17th, 1815, the eve of the Battle of Waterloo, the Duke of Wellington set up his headquarters and drafted what would become his victory dispatch from the home marked #1 at the very top of the map. Napoleon and his staff spent the night at the blue #3 at the bottom of the map.

Memorial 1815, a museum built for the 200th anniversary of the battle beneath Lion's Mound, allowed us to experience one of the world's greatest battles. Portrait of Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington:

As a result of a plebiscite, Bonaparte had himself declared the hereditary Emperor of the French, taking the name Napoleon 1, at a coronation in 1804 at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris.

France had been at war with European powers almost nonstop from 1892 until 1815 in what was called the Coalition Wars because seven varying coalitions of European governments wanted to get rid of France's revolutionary regime and then of Napoleon.

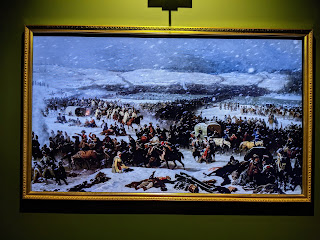

Napoleon's camp in 1809 at the Battle of Wagram, Austria:

Scene of the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805:

Some historical context: By 1815, Napoleon had been exiled to Elba by the Grand Alliance coalition of England, Prussia, Austria, and Russia, and Louis XV's brother was placed on the French throne. But in March of that year, Napoleon escaped, returned to France, tossed out the king, and restored the army to its former glory. The Alliance and the rest of Europe were in shock and pledged 150,000 troops to defeat him once and for all.

Napoleon felt his best option was to attack the allied armies individually before they had a chance to unite. French forces numbered 72,000 on the day of the Battle of Waterloo compared to just 4,000 fewer English and Dutch forces led by the English Duke of Wellington. The allies, however, had a further 45,000 Prussian troops within marching distance of the battlefield.

The defensive genius, Wellington, hunkered down atop a ridge and waited for Napoleon and his troops to advance. They did but then stopped to allow the wet ground to dry from the previous night's rain, which some say was Napoleon's fatal mistake. When they advanced again, Wellington pushed back and Napoleon was forced to send in his elite Imperial Guard. When they were surprised by the British troops who had taken cover in a wheat field, the remaining guard had to retreat in chaos. The Prussian troops attacked a nearby village and then joined the British army by nightfall.

This amazing panorama of the battlefield was made up of thousands of photographs taken during the bicentennial reenactment in 2015 when 6,200 re-enactors participated. However, digital image stitching techniques created the illusion of 26,000 soldiers to present an artistic vision of the battle in 1815.

When the Prussians captured Napoleon's abandoned carriage during the battle, they discovered it was full of diamonds. That booty became part of the Prussian crown jewels!

Although no one knows with absolute certainty how many died at the Battle of Waterloo, out of an estimated 188,000 soldiers, it was likely that 10,000 died and 35,000 were injured, not including the thousands of horses who lay dead or dying on the battlefield. Due to the lack of medical attention in the days following the battle, up to an estimated 4,000 more men died from their wounds.

There were many reports of the 'right of pillage' that took place during and immediately after the Battle of Waterloo. Prussian and Anglo-Dutch soldiers had volunteered to stay behind and strip the dead or even finish off any wounded soldiers trying to defend their possessions. The soldiers were followed by civilians, opportunistic looters, and professional grave robbers. I never knew before this that there was such a profession!

The following were sketches by C.C. Hamilton and James Rouse, British soldiers and artists who had a fine eye for detail and perspective and a sense of proportion of the battlefield the day after the battle. Their images were published in a book in 1817.

In 2012, before the construction of the Memorial 1815, an archaeological investigation took place. That was how, almost two centuries after June 18th of 1815, this skeleton of one of the combatants was finally discovered!

The Duke of Wellington in his London home designed and furnished a special gallery called the Waterloo Gallery, where all the British officers who had fought at Waterloo gathered together for the Conquerors' Banquet right up until his death in 1852.

These were the locations of cities or areas subsequently named Waterloo around the world, I, of course, immediately noticed the two in my native province of Ontario!

When Napoleon was defeated by the European coalition forces on June 18th, 1815, he returned to Paris, abdicated for a second time, and was forced to go into exile for a second time. Napoleon had hoped to be exiled in American but he was sent instead to remote St. Helena, an island in the mid-Atlantic, 1,200 miles from the nearest landmass off the west coast of Africa. The British didn't want there to be any chance Napoleon could escape again!

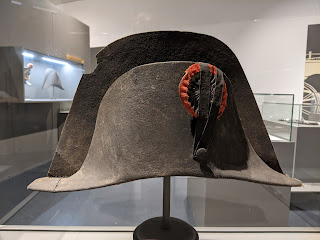

Napoleon's famous bicorne hat was nicknamed 'the little hat.' He wore it during the campaign in Belgium to set himself apart from his subordinates. About 160 bicorne hats were made by the emperor's hatmaker, about 50 of which were worn on the battlefields of Europe.

Napoleon's new home was exposed to fierce winds and, like the rest of the island, was infested with rats. After his arrival on St. Helena, he dictated his memoirs to his remaining faithful companions and offered a new perspective for future generations. Napoleon spent his days with occasional walks and less frequent horse rides, received a few visitors, took endless baths, and read newspapers and books he received from Europe.

From the end of 1819, he took up gardening to occupy himself on the advice of his doctor. When the English governor, however, increased surveillance and forced Napoleon to restrict his outdoor activities. Napoleon responded by taking on the air of a martyr, complaining about the suffering imposed by his British 'tormentor' and the European officials sent by France, Russia, and Austria to assist the governor.

Napoleon used the 19th-century crystal carafe, glass, and tea box while in exile.

His walking stick:

Since suffering skin problems from the first battles of the French Revolution, Napoleon was used to taking hot, almost boiling, baths. Through his Consulate and Empire periods, Napoleon even welcomed close allies or family members for lengthy audiences into the same room while taking baths! Napoleon used this bathtub as his illness worsened in exile on St. Helena.

The picture by the artist Steuben depicted the 'heroic' Napoleon taking his last breath on May 5th, 1821, surrounded by the last of his faithful companions. The scene of Napoleon, covered in a shroud and with the last of his 'apostles' reminded some of the almost Christian images.

Napoleon's legacy: After his death, Napoleon was glorified by Romantic artists and became the hero of European people longing for political freedom. His image spread all over the world and his possessions were venerated like genuine relics. As a result of the Civil Code and all the institutions he founded in various countries, the Napoleonic era offered the first form of unity to a Europe that had long been fragmented.

The Germans, Batavians, Italians, Spanish, and Slavs, in particular, became aware of their shared history for the first time because of joining forces against his occupation. In addition, various literary, musical, and artistic tendencies were inspired by the Napoleonic age. The beliefs of the French Revolution, spread by the Directory, Consulate, and Empire, also influenced democracy in Europe and then throughout the world, paving the way for a generation who desired individual freedom just as those in the past.

Following Napoleon's death in 1821, history was turned upside down. After being abandoned by his loved ones and forgotten by everyone after being exiled to St. Helena, his death brought him back into the public eye in a new light. Part of that was due to the texts published by his faithful companions who had joined him in exile. Their writings managed to persuade the French people who had once hated him "for his excessive ambition, the disasters of conscription and all the destruction he wrought, into a figure with eternal status. The young general in the French Revolution who became an overbearing ruler was gradually transformed into a herald of modernity and freedom."

In 1840, nineteen years after the Emperor's death on St. Helena, his body was fully repatriated to France. King Louis-Philippe and Queen Victoria agreed to allow the remains of the former exile to be brought home. When the funeral cortege arrived in Paris, his coffin was placed under the dome at Les Invalides. Another twenty years would pass before a red quartzite tomb was completed that was watched over by a dozen stone statues. Napoleon, at last, had his wish that had been expressed in his will, "I want my ashes to rest on the banks of the Seine, among the French people I loved so much."

The first panorama of the Battle of Waterloo was created in London in 1815, followed by three others built in Belgium in the late 19th century. This Panorama was a 360-degree painting of the battle that was erected in its own building in 1912 near the Lion's Mound as part of the festivities commemorating the battle's centenary.

The immense painting measured 110 meters long and 12 meters high and represented the battle about 6pm on June 18th, 1815.

The Duke of Wellington leading his troops:

Napoleon leading his troops:

The Hougoumont Farm burning in the background: More on that just below!

Perhaps some visitors might find the panorama hokey and very dated but I enjoyed being able to visualize the battle in a way the museum hadn't portrayed it for me.

We arrived just as the smoke was clearing from the canon being shot by the re-enactors.

The Lion's Mound was built between 1824 and 1826 and was dedicated to the soldiers who perished in the Battle of Waterloo on June 18th, 1815, and commemorated the spot where the Dutch Prince William of Orange, the heir to the throne and commander in chief of the first corps of Wellington's army was wounded.

A 226-step steep stairway led to the top of the Mound from where we could imagine the battlefield site might have looked back in June of 1815.

The Panorama:

Believe me, after climbing all those steep steps, we were in no rush to race right down again. We relished the chance to have a bird's eye view of what the battlefield area looked like now from all directions.

Atop the mound was an imposing 28-ton cast iron lion protecting a globe representing the earth and symbolizing the return of peace to Europe. Because the mound ruined the battlefield's geography, most historians hate it!

As interesting and informative as the Memorial 1815 (aka the museum) and climbing the Lion’s Mound had been, there wasn’t a single sign anywhere how to

reach the Hougoumont Farm where a decisive battle took place on that fateful

day. We saw people walking along a paved trail and simply followed them, not

knowing where it would take us!

Welcome to the site of the famous battle of Waterloo! It was here on Sunday, June 18th, 1815, that almost 200,000 men faced each other in the battle for more than ten hours with 35,000 horses and under fire from 500 canons. We were standing where the main line of English defense was located deployed by the Duke of Wellington over more than two miles. From 4pm onwards, seven or eight charges of more than 8,000 French led by Marshal Ney assaulted this line mostly from here for two hours under allied artillery fire. However, the French were unable to break through the English army's defensive square formations.

We knew we were on the right track when we saw a horse and buggy transport visitors from what could only be the farm to the memorial!

This stone marked the last position of G Troop Royal Horse Artillery which took a conspicuous part in defeating the attacks of the French cavalry.

A little further on, in this lane along the ridge, Wellington chose to position his forces because they gave cover for his men and made it more difficult for enemy troops to attack after tiring from climbing the slopes. In addition, heavy rain the night before had made most of the terrain muddy and difficult for exhausted soldiers to negotiate. As we walked alongside the fields, we noticed the terrain wasn't quite as flat as it had initially appeared.

It was here at 7:30pm the French army's elite battalion, the Imperial Guard was unleashed but had to withdraw after heavy fire which was the symbol for the rest of the French army to retreat. About 8pm, the Duke of Wellington advanced his troops to victory.

About a 30-minute walk from the Lion's Mound was the Hougoumont Farm which was chosen by Wellington to complete his defenses in the west.

It was here that Napoleon had launched his first attack on June 18th at about 11:30 with the aim of making Wellington withdraw from the center of his defense. The farm was key to Wellington’s victory as, just prior to the central battle, the British reinforced the brick buildings. The French weren’t able to directly attack the British and allied forces because of sustained fire from the farm.

At one important skirmish, 40 French soldiers poured into the farm through these gates but just 10 English and Scottish troops managed to close the gates behind them and all the French inside were routed. At the end of the day, more than 6,000 soldiers died at the farm. Wellington was credited with saying, “The success of the battle turned upon closing the gates at Hougoumont.”

According to a Waterloo dispatch, "The (British) army never upon any occasion conducted itself better."

The modest Chateau de Goumont, later renamed ‘d’Hougoumont, was probably built in the 15th century with a tower rising above the other buildings. During the battle on June 18th, 1815, the chateau was gutted by fire and demolished soon after the battle. Depending on what we read, the remnants we saw were what remained or were mostly a restoration.

Displayed at the farm was a remarkable group of badges, buttons, insignia, official and personal documents found near the farm after the battle.

The barn, typical of its period, was the most imposing structure at Hougoumont. A wall inside separated the wagon area from where the harvest was stored. The barn became an inferno during the battle with the roof destroyed and the walls badly damaged.

The most moving place at Hougoumont was the chapel where a finely carved late 16th-century wooden crucifix hung above the door. According to one of the celebrated stories about Waterloo, the chateau caught fire from the French shelling and the flames burned through the door into the chapel, consuming Christ’s feet, but then the flames died away!

The Gardener's House:

Now there were open fields beyond the garden walls. Back in 1815, there was a large orchard with mature fruit trees, enclosed on three sides by thick hedges. We could almost see the Lion's Mound in the distance and imagine the fighting that took place there on what was then a flat spot.

This chestnut tree, the symbol of those trees that once stood here, was planted in May 2019 to commemorate the 250 anniversary of the birth of the Duke of Wellington and in memory of the men that died at Hougoumont.

We had learned the major turning points in the Battle of Waterloo were Napoleon’s delay in not forging ahead in the muddy terrain, the timely arrival of the Prussians to join with the British troops, the relentless cavalry attacks from the British on one flank and the Prussians on another, the final charge of the Imperial Guard being surprised by the waiting British soldiers literally in the field, and the siege of this farm complex at Hougoumont. The latter was called a battle within the battle.

The walk back to the museum gave us plenty of time to reflect on the horrific Battle of Waterloo, the far too many lives that were lost, and how this one battle changed the course of history for the European continent.

After waiting for 55 minutes for the return bus to Brussels, we paid particular notice to the church in the town of Waterloo several miles north of the battlefield.

Next post: Brussels' Magritte Museum showcasing the Belgian native's surrealist art.

Posted on September 22nd, 2021, from Bruges, Belgium, where we arrived late this morning from Antwerp. In just a few hours this afternoon, we were absolutely charmed by the abundant chocolate shops, more exquisite lace and tapestry shops, and enough canals to rival Amsterdam! We can't wait to discover more in the days ahead here.

No comments:

Post a Comment