About thirty miles west of the fascinating inscriptions on the cliffs of El Morro National Monument, where Steven and I had started our day, was the Zuni Pueblo Visitor and Information Center. We had made a reservation to take a tour with a tribal leader, the only way to access Zuni land.

Kenny Bowekaty described himself as a tribal elder and the Pueblo's longtime archaeologist. He added that in 1530, "three Spaniards (after landing in Texas) embarked on a trip with an African slave who helped with encounters with compatriots in the Southwest." The Zuni's first place of contact with the Spanish Conquistadors was at their nearby ancestral village of Hawikku in 1540. He told us that the 1631 Catholic mission in his Pueblo was one of three established during the Spanish Entrada. The word "Zuni" was given to them by the Spanish conquistadors, but their official name and their language are Ashiwi.

They consider their origins to have begun approximately 225 million years ago in the Triassic Era, and they eventually settled in Hawikku, a dozen miles southwest of the current Zuni Pueblo. As of 1075 AD, it is called the Middle Place of Mother Earth, and it is the origin of the Aztecs and Mayans, according to Kenny. He also described the Zuni as a "lunar-following tribe" from the area around Ribbon Falls in the Grand Canyon - I failed to understand from him the physical or geographical connection between Hawiku and the Grand Canyon.

Kenny didn't specify the period, but hundreds of years ago, Zuni messengers were sent to other pueblos to learn different languages and serve as middlemen in trade. Salt, in particular, was traded as it was a valuable commodity throughout the Southwest.

The Visitor Center's collection included ceramics from 500 to 1375 in the first photo and from 1375 to 1600 in the second.

As Kenny drove us along Zuni Pueblo's main street toward the Pueblo, he explained that the Zuni Pueblo was the largest inhabited Native American community in the Southwest. He stated that the federally funded tribe had chosen not to participate in gaming revenues from casinos like some other tribes, preferring to concentrate on revenue from the arts sold at the trading posts. Eighty percent of the community thrives on the arts industry because they see themselves as keepers of Mother Earth and her resources, which precludes gaming. Kenny added that his people perceived the gaming industry more as a handout than a sustainable source of income.

A sign on entering the "Middle Place" indicated that recordings of cultural practices were not permitted in the "sensitive cultural area." I had purchased a photo permit at the Visitor Center to take these photos.

Views of the historical Zuni village, also known as the Middle Place and Halona Idiwanna:

The area we saw in the Pueblo didn't appear to have homes for the two to three thousand inhabitants, Kenny said, which was the Pueblo's population.

I had read in the Visitor Center that the Old Zuni Mission was established in 1632 by Spanish missionaries, but it was built with Zuni skills and forced labor. It burned during the Pueblo Revolt and was rebuilt and expanded in the early 1700s. After time and neglect again took their toll, a major assessment ascertained that extensive moisture problems threatened the building's stability. State and federal funding were secured to address drainage issues and wall remediation.

A richly ornate altar, including statues of San Miguel and San Gabriel, was created around 1776. After the Franciscan missionaries withdrew from Zuni and the region in 1821, following Mexican Independence, the Mission entered a steady decline with no permanent Catholic presence. By the early 1920s, anthropologists and others had "removed" most of the Mission's artistic and architectural features.

The statue of San Miguel, carved by Spanish cartographer and artist Bernardo Miera y Pacheco in 1775, was taken, or possibly stolen, by James Stevenson in 1880 and placed in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. The late Zuni leader Robert E. Lewis initiated repatriation in 1987. It was finally returned in late 2004 after 124 years. After future Mission renovations, the original altar will be recreated as much as possible, including the repatriation of items that have been removed over the past 130 years. Exhibits and models are planned to portray the Mission's history and the impact of outside cultural influences on the Zuni people, according to information I read in the Visitor Center.

In the 1960s, a joint effort by the National Park Service, the city of Gallup Catholic Diocese, and the Zuni Tribe restored the structure of the Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, also known as the Old Zuni Mission. Since then, it has gained fame for its vivid mural depictions of Zuni Kachina figures, painted between 1971 and 1992 by Zuni artist Alex Seowtewa. The paintings depicted the seasons and important events of the Ashiwi calendar, including a ten-day fasting period, the Council of Gods, the community's responsibility to teach others, and to learn prayers and songs. He explained that the Zuni people have a six-hour oral tradition held yearly by four Priests of Time, whose role is to teach other men the deities. Kenny said there are no services held in the Mission church.

Unfortunately, my photo permit still didn't allow me to take pictures of anything in the Mission's interior, according to Kenny. Our tour had been enlightening and informative, but somehow lacking at the same time. As you must have figured out by now, I'm a glutton for information, and he didn't provide as much as I at least would have liked.

I don't remember coming across military graves except in a National Military Cemetery.

We hoped to glean more knowledge and understanding from the Ashiwi Awan Museum and Heritage Center, a Zuni museum that initially appeared closed and had no signage, but turned out to be quite fascinating.

The Welcome sign stated immediately that the Ashiwi people face many challenges in today's world, with those roots lying in the history of their relationship with the outside world.

According to archaeologists, the Ashiwi's ancestors have inhabited the areas of their homelands for over 7,000 years, with the first ancestors roaming in small groups following and hunting big game animals. As the population slowly increased for the next five thousand years, their people lived in small groups, collecting wild plants and began practicing agriculture. About two thousand years ago, their ancestors lived in pit houses, started making pottery, and increasingly relied on agriculture for food. Within two hundred years, a rising population led to communities of larger houses.

The Zuni believe that their ancestors emerged from the Sun Father's two Bow Priests, from the Fourth Underworld at a place called Ribbon Falls in the Grand Canyon. Although their ancestors initially looked very different, the Bow Priests altered their appearance to resemble the way they look today. As soon as they were rested, their people set off on a journey to find Idiwan'a or the Middle Place, journeying through much of the Southwest. Finally, their ancestors arrived at Halon:wa, the Middle Place, and have remained in this area ever since.

I had to smile when I saw the rock etching made by Don Juan de Onate at El Morro, which he passed by in April 1605, as we had just seen the original a few hours ago!

By 1629, Spanish Franciscan missionaries had the Ashiwi build missions at Hawikku and Halona:wa, which are now located in present-day Zuni. The more or less permanent Spanish presence among the Ashiwi people allowed their ancestors to learn new ways, including language, religion, new construction technologies, and new foods such as wheat, tortillas, peaches, and the domestication of animals. The museum made a point of acknowledging these positive elements.

However, the attempts at cultural and political domination were resisted by the Ashiwi people. Efforts to build structures larger than anything traditionally built, like Mission churches and buildings, were rarely voluntary. On at least two occasions, the overzealous ways of Catholic missionaries resulted in the burning of mission churches and the killing of priests and soldiers by the Ashiwi ancestors. Even an attack by Apache on the Hawikku mission was believed to have had collaboration from Ashiwi. This turbulent time of resistance among the Ashiwi and at other regional pueblos is known as the Pueblo Revolt of 1680.

Fast forward to the late 1970s, when the museum reported that the Zuni helped bring about increased dialogue between Native American tribes and cultural institutions in the US. The Zuni religious and political leaders worked to secure the return of the Ahayu:das, or War Gods (relics?), that had been "stolen" over the years from various shrines. To date, 102 Ahayu:das have been returned from both public and private collections to the Zuni. In addition, Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act due to the diligence of the Zuni and other Native American peoples. The act permits native communities to regain control of human remains and religious and cultural materials taken from them and held by public institutions and museums. I couldn't help but think of the multiple US and foreign museums that are also now being forced to return items belonging to other cultures. The Zuni have also won decisive legal victories over land rights.

I appreciated how the museum provided a more thorough explanation of the Zuni heritage and the accomplishments made by its leaders in returning items belonging to the people, as well as the legal victories they sought and won. Fortunately, we'd done our homework and knew of the museum's existence. I feel that Kenny should have recommended that we tour the museum, as it was a secret kept too well and a great resource about his people.

Have you ever seen a lonelier road in your travels? Come to New Mexico and you'll see plenty like this, I promise you!

We detoured briefly to Quemado, described as "little more than a wide spot along the highway," but it was the starting point of an unlikely work of land art called The Lightning Field. In 1977, sculptor Walter de Maria installed 400 stainless steel poles in a grid measuring a mile by a kilometer. I know, strange measurements, right! The idea was to see the light glinting off the poles during summer storms, "creating a field of cackling, brilliant electricity across the pointed tips." Steven and I love oddball attractions like these, but we had to give it a pass as it would have involved a longer time commitment than we had, as it was out of town and meant a guided tour to the installation.

With a leap of faith, I left several birthday cards in Quemado's tiny post office. I found out today on our older son's 35th birthday that at least his was received!

Our journey continued as we passed the Continental Divide for the first time that day.

After hearing of Pie Town from Ellen, Nan, and Sarah, Steven and I had to include a stop at the intriguingly named place! To call the community a "town" is an exaggeration, as its population is only about 45. The place got its name in the 1920s when an entrepreneur began dishing out pies to hungry homesteaders, and later to cross-country motorists. When the interstate diverted traffic, the pie market dried up, and Pie Town went pie-less for decades.

We'd planned on scarfing down a slice of pie at Pie-O-Neer Cafe, but it was closed that day.

I recommend clicking on the pictures to make them larger for an amusing read.

Fortunately, our quest for pies was answered a couple of hundred feet down the road at The Gatherin' Place, which was doing a rip-roaring business at the intersection of Key Lime Road.

The waitress - I just can't be politically correct in this place and call her a server - said they sell 80 of the 6" pies a day, but none with ice cream that day, sadly. One of their staples was New Mexico apple with chili and pinon nuts. Steven and I wimped out and had a plain apple one. What did you all enjoy, Sarah, Nan, and Ellen?

The baker next door to the full-serve restaurant was cranking out pies as fast as she could!

Our next stop that day was a long haul away, with strange structures jutting out on the Plains of San Agustin from a long way off. The 27 radio telescopes, which resembled enormous satellite dishes, comprised the Very Large Array, a research center dedicated to the study of deep space. The long access road to the Visitor Center:Fortunately, Steven just noticed the deer scampering across the road in time.

8

Eight years later, a national group of astronomers recommended that a large, multi-antenna radio telescope be built as a national facility and available to all astronomers.

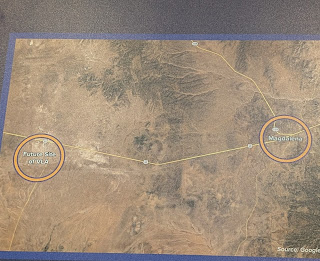

After a three-antenna prototype was completed in West Virginia in 1967, NRAO scientists and engineers began developing equipment and techniques required to build a much larger array of telescopes. Following an extensive, multi-state search, a committee of the National Research Council and the National Academy of Science recommended that the Very Large Array (VLA) be built on the Plains of San Agustin west of Socorro, New Mexico. (We'd stay in and visit Socorro later on this trip.) Once the first 230-ton antenna was completed in 1975, the first astronomical observation was performed at the VLA.

I'm the farthest thing from a science nerd or geek, but here goes, thanks to the display in the Visitor Center. Once multiple antennas are connected to a correlation receiver, signal processing combines them to allow the 27 25-meter telescopes on the VLA to function as a single unit.

The VLA opened to research use by scientists from around the world while it was still under construction, and it was formally dedicated in October 1980.

Scientists using the VLA in 1994 discovered the first "microquasar," a smaller yet equally powerful cousin of supermassive black holes found at the cores of distant galaxies.

Radar signals bouncing off Mercury and captured by the VLA provided the first high-resolution radio image of the planet, revealing the presence of water ice at Mercury's poles.

Einstein was right: In 1987, the VLA captured a radio image of light from a distant object that was first deflected around a closer galaxy. It was the first image of an Einstein ring that he had predicted in 1936. Gravitational lensing is now used to study a wide range of phenomena, from dark matter to the age of the universe.

Some of you may remember the 1997 movie Contact starring Jodie Foster and Matthew McConaughey. As much of the action was filmed at the VLA, it spurred an increase in tourism to the Visitor Center.

I found it fascinating to learn that, long after its dedication, the VLA remains at the forefront of science as one of the world's most powerful tools for unlocking the universe's secrets. Not surprisingly, the Next Generation Very Large Array (ngVLA) is already underway.

After walking around the excellent Visitor Center, we took a self-guided tour around the VLA. Why here? We learned that it was located all the way out here on the Plains of San Agustin because it is a dried-up bed of an ancient lake, and, as we could attest, flat for 55 miles and far away from any city! The large, flat area on the Plains allows for proper placement and easy movement of the antennas. The mountains surrounding the Plains provide protection from man-made electrical interference. The height above sea level also minimizes the blurring effect of he atmosphere on radio images.

I probably should have known, but didn't before our visit, that the universe is filled with fascinating and often hidden objects that emit invisible radio waves. Those are scooped by the VLA as they land on Earth. Each 82-foot VLA dish is a parabola, a special shape that bounces waves to a single spot called a focus. A second reflector is used to bounce the collected waves to the focus inside a receiver. Those waves are converted by the receiver into an electronic signal that travels to a special-purpose supercomputer, where it is combined with signals from the other antennas.

How big was each dish? The half-circle on the ground in front of us was 82 feet across, the same diameter as the dish on a VLA antenna, or the same as two school buses parked end to end.

The tent-shaped antenna was an example of the antennas that comprise the Long Wavelength Array or LWA. Like the VLA, it also combines data received by individual antennas into impressive radio images of the sky. Although the LWA cannot move to image different areas of the sky, it can observe the entire sky at all times and utilize sophisticated, cutting-edge software to target specific objects that scientists wish to study.

The VLA is kept running thanks to a dedicated team of engineers, electricians, and mechanics who maintain the world's busiest and most versatile telescope. The VLA is in operation 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, except on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year's Day.

Perhaps like me, you're wondering what the VLA does? Radio waves captured by the VLA reveal the dusty birthplaces of stars and planets, violent collisions between distant galaxies, and powerful outbursts from around black holes. With the VLA's giant eye on the invisible universe, it has witnessed many new wonders of the cosmos.

Why is the VLA so large? Each of the dishes was actually larger than the world's largest optical telescope. However, one VLA antenna cannot see as clearly as its optical counterpart. That was because bigger telescopes reveal finer detail or greater "resolving power," as astronomers refer to it. With radio waves much longer than light waves, a much bigger telescope is needed to resolve finer details.

The connected array of 27 telescopes has created a telescope that is 22 miles in diameter, thereby rivaling the resolving power of an optical telescope. The array of 27 radio antennas spans a huge "Y" shape, called a Wye. Every four months, the antennas are moved to different stations along each arm of the Wye to map finer details.

Inside a VLA antenna: Up close, it was clear that each antenna weighs 230 tons! Mammoth gears turn the dish around and move it up and down to aim at sources of natural radio waves in space. These giant 82-foot-diameter antennas were specially designed for the VLA, with the dish's aluminum panels formed into a parabolic surface accurate to 20 thousandths of an inch!

Every antenna in the VLA can be picked up by one of the two giant Transporters and hauled over the train tracks, either for maintenance or to change the array's size. The transporters, specially designed to negotiate 90-degree turns onto spurs at each antenna station, carry the antenna on 39 miles of double-standard gauge track. The flat area of the Plains of San Agustin was a perfect site for the railway tracks that carry the VLA's giant, movable antennas.

It was impossible not to be in absolute awe of the brilliant scientific minds that conceived of, and built, the Very Large Array, and who conduct research into the Universe. Touring the site on the Plains of San Agustin was a helluva thrill, even for two non-science geeks!We still had a 90-minute drive ahead of us before reaching the Palace Hotel in Silver City that night! Fortunately, sunset in western New Mexico wasn't til close to 7:30, so Steven didn't have to drive in the dark.

After eating at one of the few watering holes still open, we wandered around Silver, as it's known to the locals.

The Palace Hotel:

A few shots of the main drag before we both collapsed:

Next post: Exploring Silver City during the light of day and lots of scrambling at the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument.

Posted on May 27th, 2025, on our last night on the road from amazing Albuquerque, New Mexico. What a fantastic road trip this has been - we are thankful for those of you who inspired us to tour our neighboring state in far more depth than we had ever previously considered. New Mexico, also known as the Land of Enchantment, should be on everyone's travel wish list. We were already planning to return to Las Cruces in the southern part of the state, but now we'll also add more time in Albuquerque next spring, too, God willing. Take care of yourself and your loved ones, do what makes you smile, and help make someone else's day a little brighter.