Just a few minutes' walk from the apartment Steven and I'd rented in Milan was one of the city’s most historic, religious, and artistic sights, the Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio. The church was built atop an early Christian martyr’s cemetery around 380 AD by St. Ambrose. Milan was then the capital of the fading Christian western Roman Empire and Ambrose, a local bishop, was one of the great fathers of the early Church.

This Daily Travelogue is a labor of love for our families and friends at home and around the world. Prior to 2020, all our trips were documented on separate, yearly blogs which can be accessed below. Remember that clicking on any picture will open it for better viewing. Also, please consider adding your name at the end of any comments. Be safe, stay healthy, and stay connected.

Friday, November 26, 2021

10/14/21: Milan's Basilica di Sant'Ambrogio & The Last Supper!

Rather than stepping directly into the church, the entrance was through the arcaded atrium which was standard when so many churches prohibited people from entering until they were baptized. During Mass, the unbaptized remained in the atrium.

Over the golden altar was the ciborium or canopy which protected and enclosed the altar that had been ordered by Bishop Lorenzo after 494 AD. In the ninth century, four porphyry columns were added to the precious canopy. Thank goodness, all of it was removed to the Vatican for safekeeping during WW II as the apse took a direct hit in 1943 and a 13th-century mosaic was destroyed.

The Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament was closed to visitors.

Under the altar was the crypt that contained the skeletal remains of St. Ambrose and two earlier Christian martyrs he'd visited prior to building the church. The crypt was built in the second half of the 10th-century with more work done in the 19th-century following the moving of the three bodies or holy relics from a nearby church. The relics were contained in a silver urn created in 1877.

Ambrose himself disinterred the remains and solemnly buried them under the basilica's altar in a tomb lined with precious marbles he had also prepared himself. When he died in 397, Ambrose was buried in another tomb by the two martyrs.

Back up in the church was the ambo or pulpit for the reading of the Gospel. It was held up by ancient columns that rested on a famous Early Christian sarcophagus that was created in the late 12th-century. The pulpit was used by the canons and monks for liturgical functions, singing, and sacred readings and is still used to this day for solemn ceremonies.

The complex decoration covering the ambo was largely inspired by Ambrose's writings and dealt with the theme of sin and redemption. One scene was carved with a banquet with eleven guests that was thought by some scholars to represent the Christian Agape, the ritual dinner the first Christians held every Sunday evening. Others interpreted the scene as The Last Supper.

The plinth or base was one of 26 columns, 13 to a side, which lined the central nave in the original basilica that dated to the Ambrosian period of the end of the 4th-century. It was only discovered in the 19th-century during renovations.

The mosaic in the apse depicted Christ Pantocrator or All-Powerful surrounded by Milanese saints.

Throughout the church were pillars with Romanesque capitals and a few surviving fragments of 12th-century frescoes that had initially covered the entire church.

Crowds would be blessed by the local bishop from the upper loggia.

The entrance area of the Chapel of the Dying St. Ambrose that had once been dedicated to the Holy Sacrament was completely repainted in 1737-38. The altarpiece was called the Last Communion of St. Ambrose.

I hope you could get a sense of how stunning the basilica was from these photos and descriptions.

The primary reason Steven and I wanted to visit Milan was to view The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci. Everything else, like the Duomo, its museum, and the basilica, was gravy even if it were the richest gravy possible. Several weeks previously we’d purchased timed tickets to enter the Church of Santa Maria delle Gracie to view one of the most important artworks in the world.

Some background: The Sforzas, Milan’s leading family, hired Leonardo to decorate the dining hall of the Dominican monastery adjoining the church as Dominicans traditionally placed a Last Supper image at one end of the dining hall or refectory and a Crucifixion at the opposite end. Da Vinci worked on the fresco for four years beginning in 1494. I read that the Sforzas wanted The Last Supper painted in the dining hall as a ‘bribe’ to the monks so they would allow the Sforza family tomb to be placed in the church. However, once the French drove the Sforzas out of Milan, they were never buried in the church and the monks received a great fresco at no cost!

After waiting in several dehumidifying chambers to minimize damage from humidity, only 30 tourists were allowed into the refectory hall for exactly 15 minutes.

The photo showed damage to the church from a bomb that fell during WW II and the first attempt to secure the church's paintings after August 1943.

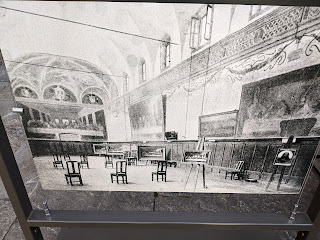

The church's refectory after restoration works in 1915:

Though the concept of setting up a study and visitor area in the Santa Maria delle Grazie refectory dated to the beginning of the 1800s, nothing came of the plans until the mid-1800s. In 1819, it was even suggested that The Last Supper be detached from the wall and moved. But, by the end of the century, the refectory walls were paneled in wood to create a Renaissance-style setting.

The refectory in 1895 with a sequence of copies and the painting of The Last Supper on the far wall:

When Italy joined WW I in 1915, plans for the museum had to be put on the back burner as war demands took priority. After the refectory was stripped of the works on display, it was used as a Red Cross hospital. Fortunately, Leonardo's work was among the first to be secured with drapes soaked in fire-retardant and constant night-time surveillance. Though Milan only suffered one bombing during WW I in 1916, attacks in 1943 were devastating.

As soon as the war ended, work began on rebuilding the hall from the rubble even though the idea of turning the site into a museum was not immediately resumed. During the fifties, the taste for historical settings declined and the 19th-century wood paneling was removed. The refectory was then seen as a neutral backdrop, completely bare except for a few antique choir stalls against the side walls. That way, visitors could contemplate the masterpiece which would be a symbol of the city's rebirth.

Once the last door opened, the immense painting was before us and I remember feeling I was in a hallowed space. It was far, far larger than I anticipated having seen hundreds of images over the years.

Fifteen minutes was a long time and yet it went by so quickly, especially knowing this would be our one and only opportunity to view the great work.

As Leonardo painted on the wall in layers, the same as he would a canvas, the fresco began to fade within six years. If da Vinci had applied pigments to wet plaster in the traditional fresco technique, the masterpiece wouldn’t have begun deteriorating and literally peeling off now. It seemed like an act of God the fresco was spared when the church was bombed in WW II. A 21-year restoration that was completed in 1999 removed 500 years of touchups.

We could feel how Leonardo captured the drama among the apostles after hearing the Lord’s words that one of them would betray him. Simon on the far right gestured as if he were asking a question that had no answer. To his left were the apostles Matthew and Thaddeus.

The only one not appearing shocked was Judas, fourth from the left, and the only one with his face obscured, as he clutched his thirty pieces of silver.

Next to Jesus was the doubting Thomas.

Just as the monks ate in silence and communicated in hand gestures, it was hard to miss those in Leonardo’s composition.

The walls were lined with tapestries just as they would have been with the one on the right brighter in order to match the refectory’s actual lighting with its windows on the left.

Bartholomew, James the Lesser, and Andrew:

I had read of the importance of the circle meaning life and harmony to da Vinci. That was why the 13 characters were positioned in a semicircle, with Jesus in the middle, so that the spiritual force of God could spread out to the edges.

Travel writer Rick Steves noted that Jesus was portrayed anticipating his sacrifice with even his feet foreshadowing his death by crucifixion.

It was hard not to be shocked upon hearing that Napoleon's men used the refectory as a stable and barn in 1799.

To guarantee its conservation, a sophisticated protection system safeguards the painting against variations in temperature, dust, and polluting agents. In 1980, UNESCO granted World Heritage status to the Santa Maria delle Grazie complex.

At the opposite end of the refectory was The Crucifixion fresco from 1495 by Giovanni Donato da Montofano, a Milanese painter who used the traditional fresco painting technique. That explained why it was much better preserved. Because it had to be done quickly as the plaster dried, it was created with less subtlety than The Last Supper. It was painted in just three months compared to over three years for the latter.

Represented in the fresco were saints and 'blessed souls' of the Dominican order with the city of Jerusalem in the background. The group at the foot of the cross was composed on the left of Mary Magdalene, St. Dominic, the founder of the Dominican order, and St. Thomas Aquinas on the right.

On the right of the fresco were the Duke of Milan and his consort, both probably painted by Leonardo at a later date.

I was so impressed that there was a tactile bas-relief of The Last Supper so visually impaired visitors could also appreciate the stunning work.

We took one last look before leaving, trying to imagine the room filled with four tables and sixty monks 500 years ago never thinking their space would be ‘invaded’ by tourists appreciating the art.

After leaving the refectory, we again had to exit via several rooms to dehumidify. I thought it was a perfect downtime to relish the beauty of what we had just viewed.

Next to the refectory was the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie that survived unscathed in WW II.

The black-and-white frescoes under the pilasters depicted the first monks to dine under Leonardo's The Last Supper.

A final respite in the church's cloister:

Next post: Milan's Pinacoteca Ambrosiana and more treasures!

Posted on November 26th, 2021, from Denver just a few days after returning from two glorious months in Europe and yet just days before leaving for three weeks in French Polynesia and then spending Christmas in San Francisco with our son and his family!

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

How lucky you were to SEE Leonardo's brilliant "Last Supper" ; even in the photographs you posted, I could "feel " the drama among the dinner guests we have learned about in biblical readings. Thank you for sharing and adding so much narration to the tour of the Church of Santa Maria delle Gracie.

ReplyDeleteThanks, my dear Lina, for your touching and heartfelt comments about the da Vinci post. It felt like seeing a wonder of the world. How lucky were we to view the masterpiece in real life and not just the countless images we've all viewed?!

Delete